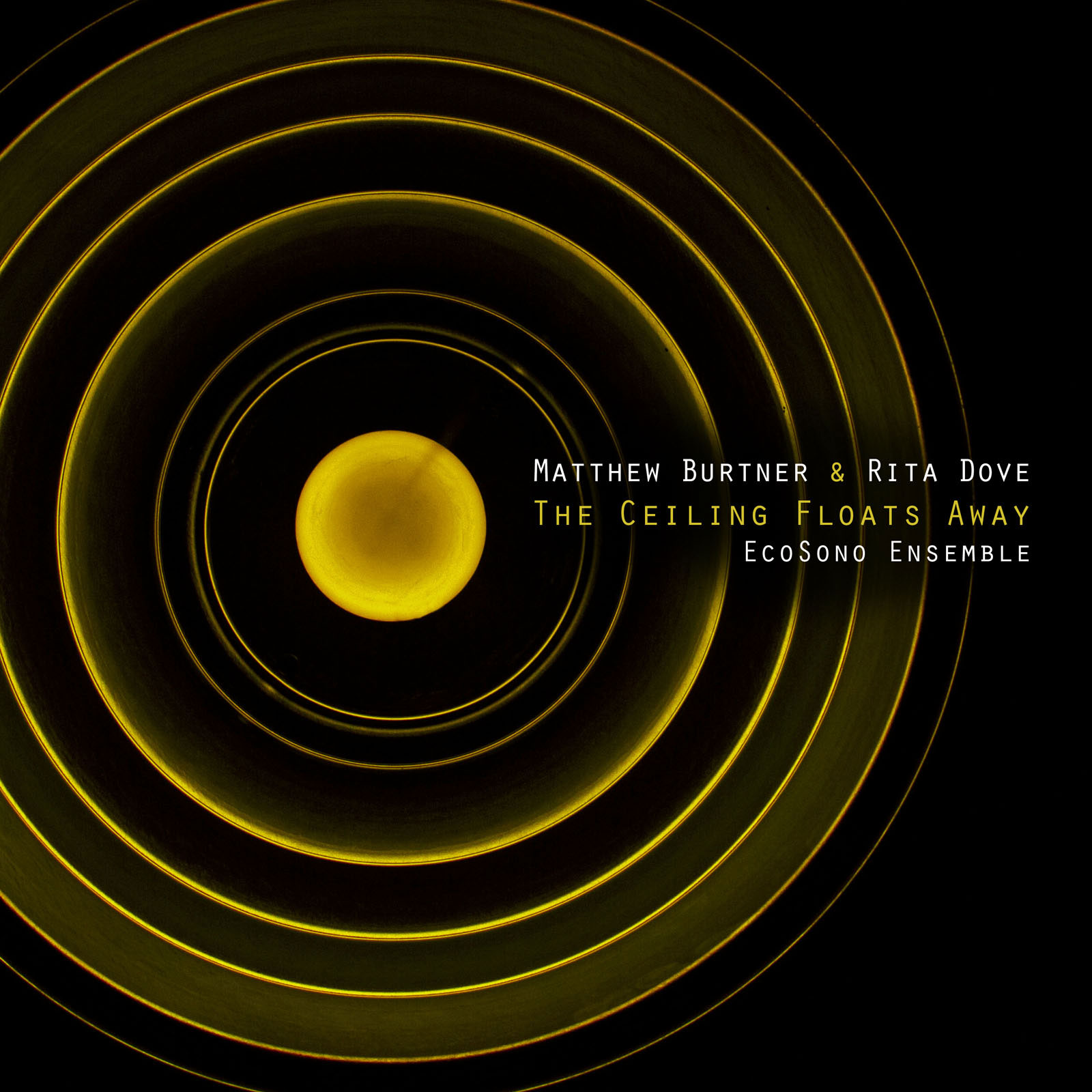

Matthew Burtner, one of today’s most innovative composers and creators, has released a new kind of musical experience: THE CEILING FLOATS AWAY. Using the cutting edge technology “Nomads,” software that enables audience participation through mobile devices, the album bridges the gap between performance and technology, audience and artist. As Burtner writes, “the piece empowers people as creative agents in an artwork without walls, without ceiling.”

Today, Burtner is our next featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our artists. Read on to see how he packed a NY venue with the help of giant pink bunnies…

Who was your favorite artist growing up?

My mom was an inspirational artist to me. She played music, sculpted, made mixed media art pieces, created quilts, etc. She lived art. She was always making something driven by creativity, whether it was for a functional or decorative purpose, for play or purely for aesthetics. When I was growing up, we didn’t buy things. We made everything.

When did you realize that you wanted to be an artist/ composer/creator?

My wonderful saxophone teacher and childhood mentor, Hal Nonneman, helped me become a composer and sound artist. I played the music for our lessons as a technical exercise but I complained about it. He tried band, classical, jazz, and pop charts, but I thought it was all contrived and underwhelming as music. Saxophone is a tough instrument. It’s not like piano or electric guitar, for which there would have been amazing music to learn. I wanted music to be more unusual, emotionally engaging, noisier, and more“real,” like the wind, snow or sea, which were big influences on my imagination as a child.

I think Mr. Nonneman got fed up with me though. One week he told me to bring back a piece of music that I wanted to play. That week I wrote my first piece. It was for left hand alto saxophone and right hand snare drum. He described it to me as “new classical music” and that’s how I thought of it too, even though I didn’t actually hear new classical music until college. I continued to play in all sorts of bands (jazz, orchestra, wind band, marching band, pop, punk, rock and reggae groups) but I also continued to make my own idiosyncratic, creative pieces for myself. Now that’s all I do.

What was your most unusual performance so far?

I’ve given a lot of unusual performances: in the sand dunes of the Namibian desert, improvising with the bore tide on the coast in Alaska, in the middle of the Indian ocean, in a secret Masonic Temple cave in Switzerland, etc. My unusual experiences could fill a short book.

One time my brother Jesse and I did a tour together. He is a leading innovator in the world snowboard videos. We were performing an experimental snowboard video with live Metasax computer music and drums by Morris Palter. It was a terrific set. This particular performance was at The Stone in Manhattan and was sponsored by a super hip clothing company called Spacecraft. Spacecraft sent two guys wearing pink bunny suits to go out onto the street to get people to come to the concert before the show. We didn’t know that was going to happen, but suddenly these giant bunnies were out on Houston Street jumping around, causing a scene, stopping traffic and waving our tour banners. People were alarmed and I think the cops intervened. Meanwhile, the Stone is this dingy little place that can only seat like twenty people anyway. It was packed and hot yet people kept coming in. It was chaos. I was trying to get all the Max patches working across the different computers (I used four different computers in shows then) and coordinated with the Metasax while people were yelling at me about these pink bunnies stopping traffic on Houston St. That was exhilarating.

In the event of a zombie apocalypse, what are the three things you absolutely can’t live without?

Sunset. Ice. Coffee.

If you could do any job in the world and make a living at it, what would that be?

I wanted to be an architect but I was obsessed with sound. I like architecture because, unlike composition, an architect can make dynamic structures that persist formally through time. In music the sound waves are always dissipating, the structure always collapsing. It’s frustrating because you build up this impressive and intricate design but when the musicians stop playing the whole thing disappears in a couple of seconds.

If you could spend creative time anywhere in the world, where would it be?

My composing table in Alaska, on the catwalk in the cabin, is my favorite place in the world. It has a window out of which I can see Denali on clear days. On cloudy days, because the cabin is high up in the mountains, I open the window and the clouds drift right in across the music paper.

What would you say to an artist performing your work that nobody else knows?

I try to make music that has a place for the creativity of the musician. I am truly interested in how different artists interpret the scores, even in ways I didn’t intend or imagine. Musicians often ask “is that what you meant?” My response is to look at the score and see if the notation allows their interpretation, then ask the musician “is that what you meant?”. I also say “let’s try to break it,” which means let’s try to interpret the score correctly in a way that yields something that doesn’t sound right.

In many of my pieces, rehearsing involves trying to interpret the notation in different ways so that we can understand the possible range of interpretations. We might find a mistake in the score which would be a way of interpreting that yields a poor result, subjectively determined. Because I compose the score imagining multiple paths of interpretation and leaving parameters open while specifying others, performers sometimes discover wonderful interpretations that brings their individual artistic personality into the piece. I love that.

What was your favorite musical moment on the album?

“Suck the good milk in.” Rita and I laugh every time we hear that.

Rita Dove (left) and Matthew Burtner (right)

Was there a piece on your album that you found more difficult to compose than the others?

Lint was quite challenging. The track is only one minute long but composing that was difficult and took many versions. I was trying to capture the feeling of a room, the ambient light on objects, the surfaces of things contained in other things, complex interiors, and always zooming in on the dust. The poem is full of evocative contradictions and complex emotions that are difficult to cast in sound: “awkward loveliness,” “small, unimaginable cold.” It’s everything I love about Rita Dove’s poetry.

What does this album mean to you personally?

For me the album is about composition and creativity. The piece itself is not experimental in its sound, not like much of my other music which pushes against common expectations of what “music” can be. But the form of the piece is radical in that it opens the creative artwork to the audience who generate the poetry and music through interaction with the Nomads software through their smart phones. The composition is porous and the audience can get into the material itself, which sort of breaks composition while simultaneously celebrating it. The juxtaposition of artist-composed poetry/musical pieces and audience-composed poetry/musical pieces showcases our theme of creativity and collaboration taking flight in the larger public imagination.

Is there a specific feeling you want listeners to tune into when hearing your work?

Imagine wandering around in a rich and intricate garden. It’s a garden of words and sounds and you can explore it freely. Ambling through the ambience, you come upon intricately composed, small pieces, like finding an exotic flower among the shrubs and shadows. This is the feeling of the album to me. The audience interaction bridges are open forms, an ambient radiance of scattered words and sounds. Then suddenly the non-linear fixes into a completely structured piece of poetry and music. The album oscillates like this, between open and closed forms. THE CELING FLOATS AWAY is a whimsical, perhaps mercurial piece, but this approach allows for a larger structure which addresses free imagination, and emergent forms through the creative process.

Matthew Burtner is an Alaskan-born composer, sound artist, and eco-acoustician whose work explores embodiment, ecology, polytemporality, and noise. His music comfortably crosses boundaries between environmental science and art, philosophy and acoustics, technology and body, and he is a leading practitioner of climate change music and ecoacoustic sound art. As a composer, Burtner seeks out contexts where critical issues of human/nature interaction are addressed, whether in musical contexts, other forms of media, scientific conferences, or political conventions. His music has been performed in concerts around the world and featured by organizations such as NASA, PBS NewsHour, the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the BBC, the U.S. State Department under President Obama, and National Geographic.