Matthew Burtner is an Alaskan-born composer, sound artist, and eco-acoustician, whose music and research explores embodiment, climate change, polymetrics, and noise. First Prize winner of the Musica Nova International competition and an IDEA Award winner, Matthew’s music has also received honors and prizes from Bourges (France), Gaudeamus (Netherlands), Darmstadt (Germany), and The Russolo (Italy) international competitions. His music has been performed in festivals and venues throughout the world, and commissioned by ensembles such as NOISE (USA), Integrales (Germany), Peak FreQuency (USA), MiN (Norway), Musikene (Spain), Spiza (Greece), CrossSound (Alaska), and others. His work has been supported by major grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Science Foundation, and he has created ecoacoustic music for the Obama State Department and NASA. He is Professor of Composition and Computer Technologies (CCT) at the University of Virginia, and Director of the environmental arts non-profit organization, EcoSono (www.ecosono.org).

Today, Matthew is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our artists. Read on to discover what this album means to Matthew in light of rapid climate change…

What inspires you to write and/or perform?

I am inspired by natural forms that overpower us, like the wind or the sea or glaciers or the atmosphere. I compose music that sets humans in direct contrapuntal relationships with those natural forms by composing music through ecoacoustic methods. My work with technology, composition, and environmental science works towards that. I am inspired by methods of scientists — the search to discover our world through experimentalism — and I imagine music as a kind of science of vibration and emotion.

If you could collaborate with anyone, who would it be?

As a composer, there is nothing better than collaborating with amazing musicians… for example when you write the note G on a page, and they play a whole world in that note! Collaboration has pretty much defined my recent work and many of my projects are created in collaboration with musicians, choreographers, poets, architects, engineers, scientists, philosophers, artists, or scholars. I have been super fortunate to intersect with some amazing people and organizations and I would like to do more with them. For example, I’d like to do more with Al Gore’s Climate Reality Group which I had the pleasure of working with in Brazil. It was awesome to compose music for Barack Obama’s State Department when he came to Alaska, and I would like to do more work that intersects with politics, particularly with the discussion of climate change. GLACIER MUSIC is aspirational in this way, imagining music as a collaborative enterprise in dialogue with science and technology to expand the societal discourse. I would like to continue to collaborate with scientists and partner my ecoacoustic approach with their experimental methodology. I’ve enjoyed some wonderful scientific collaborations and presented my music recently for NASA and at the American Geosciences Union conference where 20,000 scientists gather to share breaking research each year.

What advice do you have for young musicians?

I advise young musicians to study philosophy and travel. Young artists benefit creatively from diverse exposure early and to challenging ideas. I am skeptical of the “write what you like” approach to composition and I advise composers to challenge their tastes and biases with plurality and diversity. In general I would like to see people work on things they care about in life, to align one’s work with one’s desire to make the world better. If everybody spent their time working on the things they care about, we could turn the world around very quickly! I teach a graduate seminar at the University of Virginia on “Musical Materials of Activism,” and we start that class with a discussion about what we care about and how our work as musicians aligns or does not align with these larger life concerns. Then we explore how music can be directed to larger societal problems.

Do you have any specific hopes about what this album will mean to listeners?

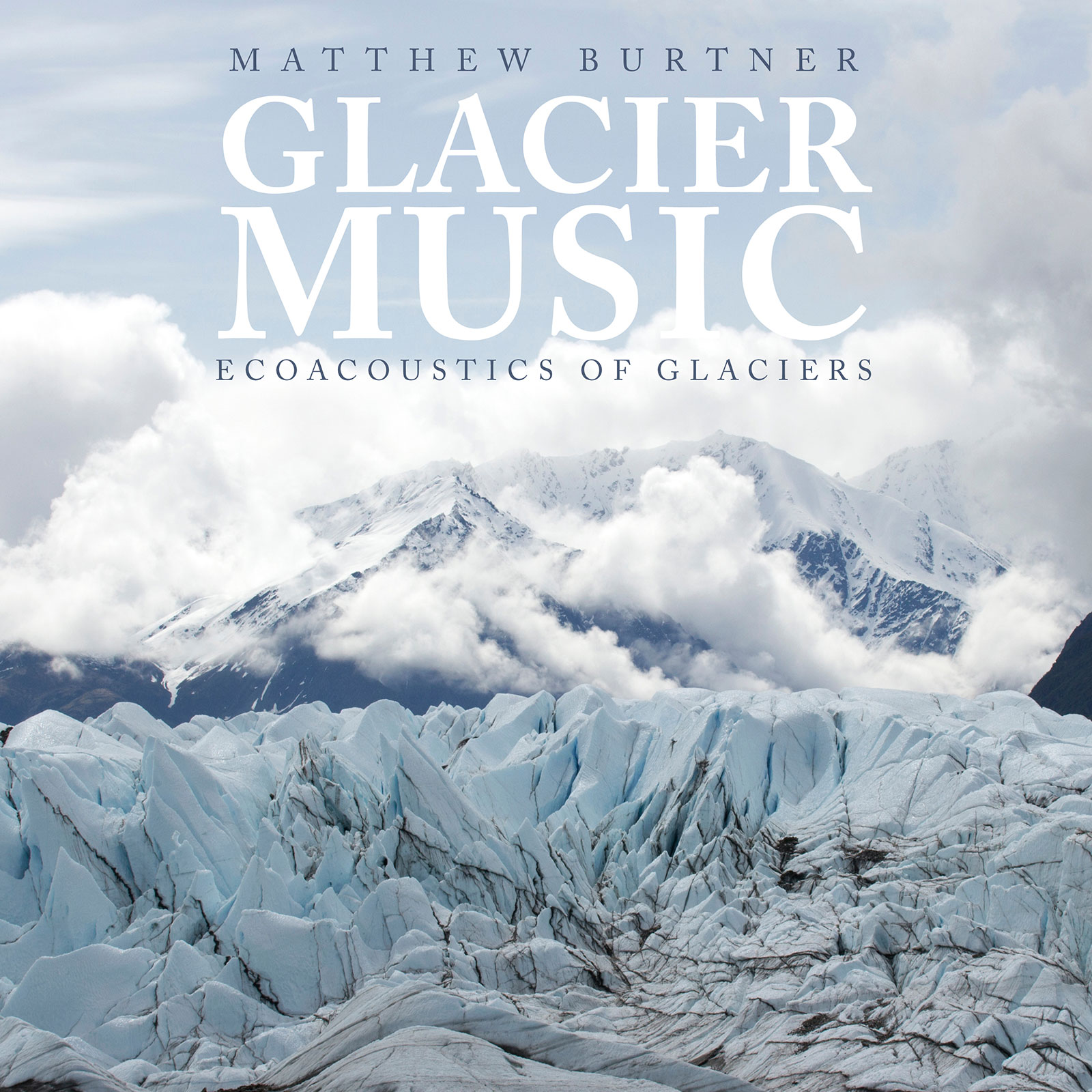

Besides being a product of my creative imagination, this album is also a kind of document from the glaciers themselves. The music creates a frame and a contemplative space for snow and ice to teach us about life. I hope listeners hear it like that. GLACIER MUSIC might become a requiem, as in a remembrance for something that was lost. When I started composing this music, I thought we might be able to save the glaciers, and that music could play a part in arresting global warming. But increasingly that seems unlikely and I hear the album now more as an active commemoration of the passing of these great earth animals. People might listen to this album in the future as a way to understand how glaciers sounded and how we felt about their rapid melting in the early 21st Century. There is a lot of science in this music, but also a lot of emotion. I think the compositions innovate in the field of music — for example with the use of snow as an instrument, the techniques of sonification, and the sound casting approach — but I hope this music will mean something outside of the field of music. I always try to make music that is sonorously effective and conceptually stimulating.

What were your first musical experiences?

They involved hearing the wind, the sea, and the snow, and singing or humming with those sounds. When I started playing saxophone I often played outdoors with the sounds of nature. Those experiences were quite formative for me as my music now sets human musicians in counterpoint with sonic landscapes.

Where and when are you at your most creative?

In my cabin in Alaska there is a catwalk that spans the main living area and my desk sits at the end of the catwalk with a window that looks north towards Denali and the sky. The cabin is up in the mountains and sometimes the clouds come right in the open window and drift across the pages of my music! It’s creatively inspiring but also distracting. Distraction can also feed creativity — composing in cafes with all the chatter and movement around; or in libraries, browsing the stacks, surrounded by immeasurable knowledge; or hiking outdoors — I find that being connected and alone at the same time is creatively inspiring. Any time of day can be a creative time, but it also takes a lot of time to produce something out of that creativity, and that’s the hard part.

Matthew Burtner is an Alaskan-born composer, sound artist, and eco-acoustician whose work explores embodiment, ecology, polytemporality, and noise. His music comfortably crosses boundaries between environmental science and art, philosophy and acoustics, technology and body, and he is a leading practitioner of climate change music and ecoacoustic sound art. As a composer, Burtner seeks out contexts where critical issues of human/nature interaction are addressed, whether in musical contexts, other forms of media, scientific conferences, or political conventions. His music has been performed in concerts around the world and featured by organizations such as NASA, PBS NewsHour, the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the BBC, the U.S. State Department under President Obama, and National Geographic.