NOWS from David Rosenboom and Sarah Belle Reid is a captivating expression of the radical challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. The music examines the notion of “co-presence,” or togetherness, when experienced in isolation. A collection of “sound correspondences” accumulated between the two artists, made with instruments ranging from strings and horns to modular synthesizers, analog signal processors, urban and desert soundscapes, and much more, NOWS is a post-genre masterpiece that speaks to our unique moment in history.

Today, Sarah Belle Reid and David Rosenboom are our featured artists on “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn about how Sarah has found rhythmic and harmonic inspiration in sounds of everyday life, and how music and physics work together to help David express his sound…

What inspires you to write and/or perform?

SBR: I have always been deeply inspired by sound. Not just “musical” sounds, but sound in general: the rhythm of dragging a suitcase across pavement, or the hum and harmony of kitchen appliances. I love exploring sounds that bridge and blur the worlds of more “traditional musical sounds” and the rich noise, chaos, and texture of the world around us. Sometimes I’ll get fascinated by just a single sound or sonic idea, and it will grow into an entire piece or album.

I also love to perform and create music because it’s such a deep form of expression and communication for me. There’s a lot that I’m not sure how I could put into words, that I feel I can easily share through music. Collaboration and co-creation are also a big part of my practice—projects like our recent release NOWS. Working with David on NOWS was very fun for me because it felt like every idea I tossed into the ring resulted in five more coming back to me, and everything was a “yes” for further exploration. I always learn so much working with others, and find the collective pursuit of something from nothing (and everything) to be very inspiring.

If you weren’t a musician, what would you be doing?

DR: From the beginning of my thinking awareness, and to this day, my interests and inspirations have straddled the arts and sciences. Music and physics drew my attention early on. The musical side eventually expanded into what we now commonly refer to as contemporary experimental music. On the science side, the physics interest expanded to include computer science, cybernetics, and now neuroscience. My life trajectory took me on many exploratory paths, but anchoring my career in contemporary experimental music became the framework inside which I could converge the broadest possible range of subjects into my practice. I am currently working on a long-term project I call concurrent complexity, an umbrella concept under which a great many things can be investigated: how we function in multimodal networked stimulus environments; how our brains work when engaged in the cybernetic feedback loops that characterize these environments; how inspiring immersive art works might emerge from this; and how they might reveal insights about ourselves, the world, evolution, and more.

What advice do you have for young musicians?

SBR: If I could sit down with a younger version of myself, I’d say two things:

1) You know those quirky ideas and awesome dreams you have—the ones that sometimes feel impossible? Follow them. Trust them. You are MORE than capable of reaching your goals (yes, even the big, scary ones!). Do something every day that gets you a bit closer to your dream, and before you know it, you’ll be there. Just keep going.

2) Practice hard, study hard, but don’t forget to play, too. Dedicate some time every day for just “noodling” around on your instrument, and see what emerges. For me personally, a lot of things started to click when I brought improvisation into my practice, and carved out time to explore different sounds just because I thought they were cool. It helped me connect the dots between all of the technique I was building on the trumpet, and how I personally wanted to express myself on my instrument. If there’s something in your practice that brings you a lot of joy, do more of it.

Do you have any specific hopes about what this album will mean to listeners?

DR: I have two hopes to emphasize. First, I hope listeners will accept and enjoy this album as an invitation to be active imaginative listeners, to be explorers in the new sonic landscapes Sarah and I have produced, to experience a profound and thoughtful joy in these explorations. I hope listeners will treat their experiences like we do, as sonic journeys of discovery, of hearing things in new ways, and of gaining skills in navigating our universe through sound. Second, I hope listeners will appreciate and understand the power of co-creative emergence, which is so fundamental to this music. This music was created through an open, egoless collaboration, where all offerings and responses were open to mutual criticality with respectful acceptance. Perhaps this might inspire new models for progressive, creative, human interactions, in which our culture might do well to engage.

What are your other passions besides music?

SBR: Aside from performing and composing music, I am extremely passionate about education. Over the years I have taught electronic music, physical computing, and music technology at a few different schools in the United States (California Institute of the Arts, Chapman University, Temple University).

I currently run an independent online course and coaching program that teaches modular synthesis and sound design, called “Learning Sound & Synthesis.” Through LSS, I have helped thousands of people from all over the world get started with electronic music, and deepen their musical practices. After going through LSS, folks have launched new careers in music, released debut albums, gone on to graduate school, performed live for the first time, and so much more… It’s endlessly rewarding for me!

Who are your musical mentors?

DR: As a youngster in the 1960s, the late great composer, Salvatore Martirano, was an invaluable and inspiring guide. I experienced the best kind of mentoring: treating each other as equals from the start, which also led to a continuous friendship lasting until his death in the mid-1990s. I have also benefited tremendously from an extraordinary list of other collaborators over many years, with whom the practice of always learning from each other was our way of being alive. This list is very long. A few non-inclusive highlights include: J.B. Floyd, Edgar E. Coons, George Manupelli, Terry Riley, Jacqueline Humbert, William Winant, Donald Buchla, La Monte Young, Anthony Braxton, Morton Subotnick, Sardono W. Kusumo, Travis Preston, . . . oh, to be fair, this list should go on and on and on, so I’ll stop. There would be too many great people left out, if I were to continue.

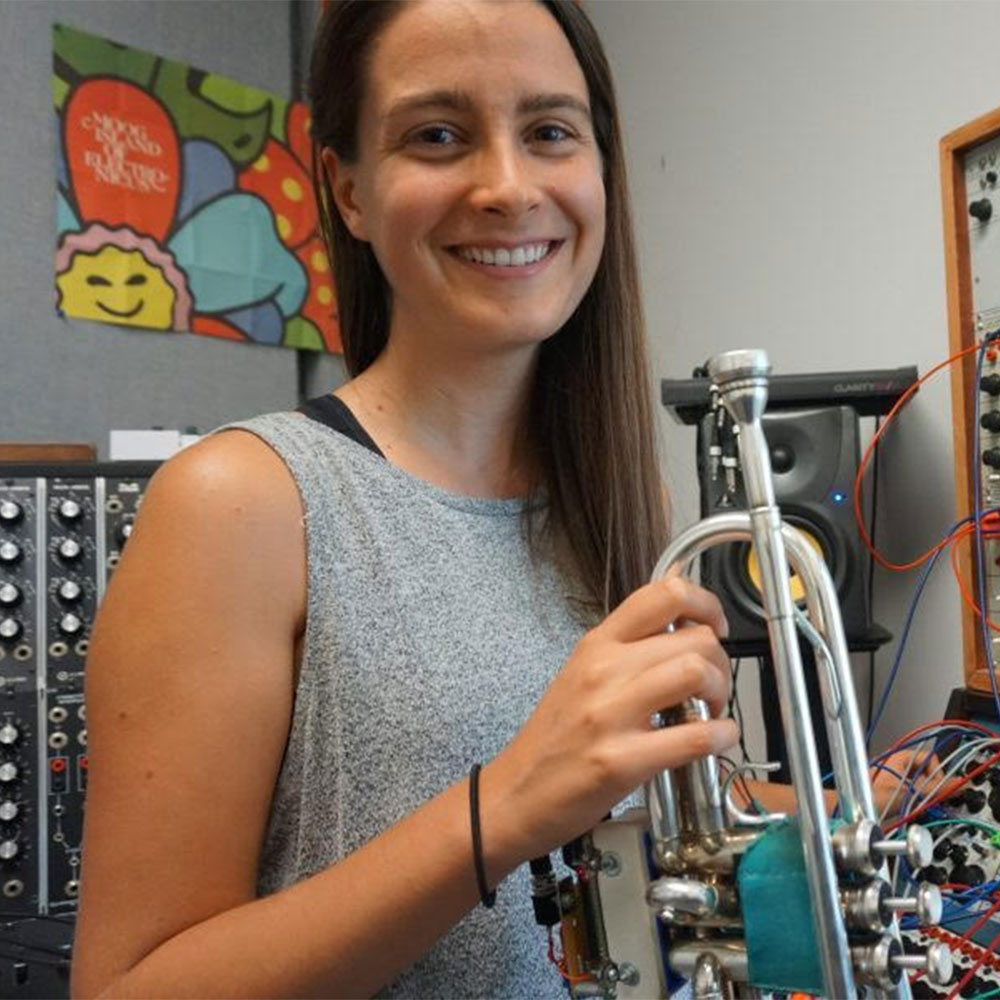

Sarah Belle Reid is a performer-composer who plays trumpet, modular synthesizer, and an ever-growing collection of handcrafted electroacoustic instruments. Her unique musical voice explores the intersections between contemporary classical music, experimental and interactive electronics, sound installation, visual arts, noise music, and improvisation. Often praised for her ability to transport audience members through vivid sonic adventures, Reid’s sonic palette has been described as ranging from “graceful” and “danceable” all the way to “silk-falling-through-space,” and “pit-full-of-centipedes” (San Francisco Classical Voice).

David Rosenboom is a post-genre composer-performer, interdisciplinary artist, author, and educator known as a pioneer in American experimental music. Since the 1960s, his multi-disciplinary work has traversed ideas about spontaneously evolving musical forms, languages for improvisation, new techniques in scoring, cross-cultural and large-form collaborations, performance art and literature, interactive multimedia and new instrument technologies, generative algorithmic systems, art-science research and philosophy, and extended musical interface with the human nervous system. He was Dean of The Herb Alpert School of Music at California Institute of the Arts from 1990 through 2020, where he now holds the Roy E. Disney Family Chair in Musical Composition.