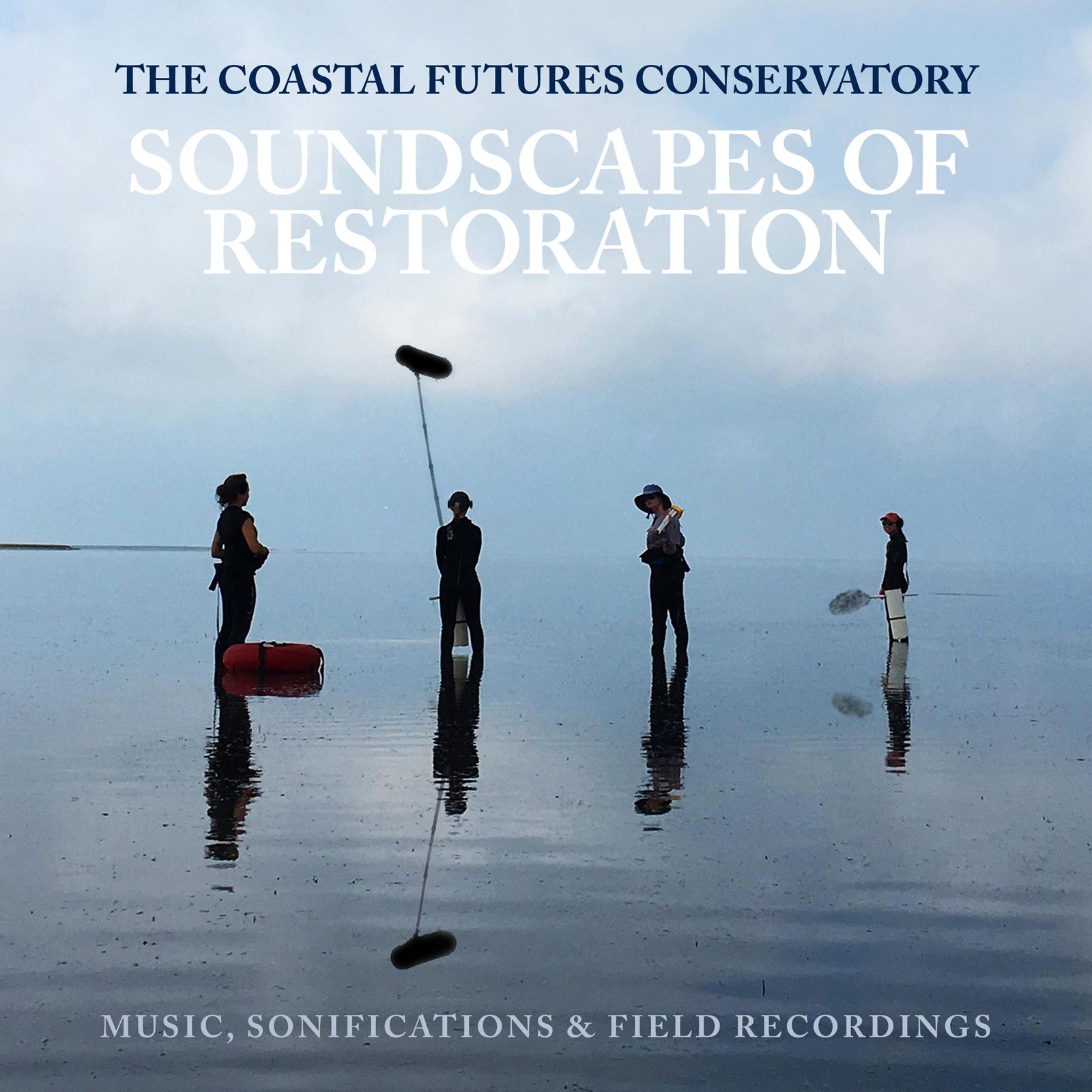

Soundscapes of Restoration

On the coasts of the Atlantic, sparrows whistle atop the trees, Eastern winds whisper through spartina grasses, and fiddler crabs skitter within their sandy burrows — a great symphony of shorelines soon to be left incomplete. As rising sea levels continue to threaten coastal reefs, shores, and the hundreds of lifeforms inhabiting them, the Coastal Conservatory urges us to consider our efforts of restoration and offers us an avenue for restoring coastal futures, a meditation on the music of the most integral barriers to the ever-pressing Atlantic. SOUNDSCAPES OF RESTORATION is both an exploration and a reflection, a listening experience that leaves one changed with the desire to make change further. It is a journey that cannot, and should not, be forgotten.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

"...this album amplifies the voices of the unheard, joining them in a musical conversation."

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Virginia Barrier Island Soundscape: Listening to Climate Change and Resilience Part 1 | 3:45 | ||

| 02 | The Dreams of Seagrasses | Matthew Burtner | EcoSono Ensemble | Siyang Sophia Shen, pipa; Kelly Sulick, flute; Glen Whitehead, trumpet; Brian Lindgren, viola; Kevin William Davis, cello; Science by Virginia Coast Reserve researchers Peter Berg, Karen McGlathery, Marie Lise Delgard, Pierre Polsenaere, Scott C. Doney, Amelie C. Berger | 5:57 |

| 03 | The Metered Tide | Chris Chafe | EcoSono Ensemble | Siyang Sophia Shen, pipa, piano; Kelly Sulick, flute; Matthew Burtner, soprano saxophone; Glen Whitehead, trumpet; Brian Lindgren, viola; Kevin William Davis, cellos | 3:37 |

| 04 | Where Water Meets Memory (Coastal Mix) | Eli Stine | 7:54 | |

| 05 | The Noise Parade/Die Lärmparade | Francisca Rocha Gonçalves | 6:11 | |

| 06 | Crab Flutes | Matthew Burtner | Kelly Sulick, flute | 5:31 |

| 07 | The Metered Tide, Refrain 1 | Chris Chafe | EcoSono Ensemble | Siyang Sophia Shen, pipa; Kelly Sulick, flute; Glen Whitehead, trumpet; Brian Lindgren, viola; Kevin William Davis, cello | 3:37 |

| 08 | Piano Étude No. 2: Tidal Flow | Chris Luna-Mega | Chris Luna-Mega, electronics (MIDI piano) | 4:26 |

| 09 | The Metered Tide, Refrain 2 | Chris Chafe | EcoSono Ensemble | Siyang Sophia Shen, pipa; Kelly Sulick, flute; Glen Whitehead, trumpet; Brian Lindgren, viola; Kevin William Davis, cello | 3:35 |

| 10 | Oyster Communion | Matthew Burtner | Mari Hahn, voice; EcoSono Ensemble, oyster shells | 5:22 |

| 11 | Fluidø Therapy #1 | Francisca Rocha Gonçalves | 6:27 | |

| 12 | The Metered Tide, Refrain 3 | Chris Chafe | EcoSono Ensemble | Siyang Sophia Shen, pipa; Kelly Sulick, flute; Glen Whitehead, trumpet; Brian Lindgren, viola; Kevin William Davis, cello | 3:34 |

| 13 | Virginia Ghost Forest Soundscape: Listening to Climate Change and Resilience Part 2 | 2:29 |

The Dreams of Seagrasses

Engineer Alex Christie

The Metered Tide, Refrain 1-3

Engineer Travis Thatcher

Crab Flutes

Engineer Alex Christie

Oyster Communion

Engineer Matthew Burtner

Mastering Melanie Montgomery

Cover photo by Cora A Baird

Introduction and Listening Notes by Willis Jenkins

Special Thanks

University of Virginia College of Arts and Sciences

Institute for the Humanities and Global Cultures (IHGC)

Environmental Resilience Institute (ERI)

Virginia Coast Reserve (VCR)

Mellon Foundation

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Chris Robinson

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming, Morgan Hauber

Publicity Patrick Niland

Artist Information

Matthew Burtner

Matthew Burtner is an Alaskan-born composer, sound artist, and eco-acoustician whose work explores embodiment, ecology, polytemporality, and noise. His music comfortably crosses boundaries between environmental science and art, philosophy and acoustics, technology and body, and he is a leading practitioner of climate change music and ecoacoustic sound art. As a composer, Burtner seeks out contexts where critical issues of human/nature interaction are addressed, whether in musical contexts, other forms of media, scientific conferences, or political conventions. His music has been performed in concerts around the world and featured by organizations such as NASA, PBS NewsHour, the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the BBC, the U.S. State Department under President Obama, and National Geographic.

Chris Chafe

Chris Chafe is a composer, improvisor, and cellist, developing much of his music alongside computer-based research. He is Director of Stanford University's Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA). At IRCAM (Paris) and The Banff Centre (Alberta), he pursued methods for digital synthesis, music performance, and real-time internet collaboration. CCRMA's SoundWIRE project involves live concertizing with musicians the world over. Online collaboration software including jacktrip and research into latency factors continue to evolve. An active performer either on the net or physically present, his music reaches audiences in dozens of countries and sometimes at novel venues.

Notes

Integrating science, music, and cultural inquiry, the Coastal Futures Conservatory creates ways of listening to coastal change. Our collaborations seek immersive forms for understanding the relations through which coasts are being remade. This album extends an invitation to listen into the future of a rapidly changing coast, with a promise that the listening itself can be a restorative act.

An ever-shifting border world of sea and land, a sea-tangled1 liminal zone where ocean and continent play through their meeting, the word “coast” already includes change in its concept. Shorelines are always being remade, so referring to coastal change can seem a redoubled concept – as if, flux of the flux-zone. Yet it rightly connotes that conditions by which coastal dynamics have played out are increasingly influenced by anthropogenic vectors and planetary forcings, which enter into complex regional combinations, relations, and becomings. Imagining “coastal futures,” then, involves scales and complexities that seem to confound comprehension. That is a central Anthropocene challenge: proliferations of scale and temporality that exceed inherited ways of making sense of our environments, and novel assemblies of relation that frustrate capacities to take responsibility for them.

Music can encompass complexities of time and scale and can express unresolved assemblies of relation. The Conservatory was founded as a partnership between music and environmental humanities scholars with scientists of the Virginia Coast Reserve — a U.S. National Science Foundation Long-Term Ecological Research site and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Long-term ecological research investigates patterns of change in particular sites over decades, which increasingly involves research on interactions between anthropogenic planetary shifts and regional systems. Ecoacoustics follows sound through ecological relations as to interpret environmental changes. Environmental humanities investigate environmental change through the archives and tools of cultural memory. A conservatory can mean a school of music, a greenhouse, or a cultural archive. We draw on all three meanings by centering ecoacoustic methods to stimulate holistic, science-based inquiry into coastal change in ways that engage cultural meaning-making.

“Music is a conservation strategy for keeping something alive that we now need,” writes David Dunn, “a way of making sense of the world from which we might refashion our relationship to nonhuman living systems.”2 We share the premise that listening across disciplines and into coastal lifeworlds can open possibilities for recomposing the relations of coastal systems. But conservation does not seem the right concept for attending to the scales and complexities already remaking coastal futures because it suggests retaining something given and potentially changeless. Responding well to coastal change will necessarily be an improvisation with changing relationships, a composition undertaken with many other change agents also making coastal futures.

SOUNDSCAPES OF RESTORATION is composed through three senses of restoration:

First, several pieces work with the soundscapes and sonified data sets of two signature ecological restoration projects in the Virginia Coast Reserve: one focused on oyster reefs and one underwater seagrass meadows. Both enhance resilience to climate change and both figure in coast-focused projects of negative emissions, or what is sometimes called “climate restoration.”

Second, each piece offers a form of cognitive restoration. The tracks restore the mind’s attention to world-making practices of non-human organisms, beings, and forces. “Arts of attentiveness remind us that knowing and living are deeply entangled,” write scholars of multispecies studies, “and that paying attention can and should be the basis for crafting better possibilities for shared life.”3 Developed from immersion — both aqueous and intellectual — into coastal lifeworlds, the “arts of attentiveness” in this album restore possibilities of understanding the living world that have been lost or missed.

Third, the album explores lines of future-oriented cultural restoration. Anthropocene relations that threaten to overwhelm cultural capacities to make sense of our worlds. “Response-ability” is Donna Haraway’s lead concept for the cultural task of inventing ways to live through Anthropocene relations: “nurturing capacities to respond, cultivating ways to render each other capable.”4 These compositions create ways to experience changing relations and compose futures within them.

Listening can help develop all three kinds of restoration. Acoustic methods of investigation have led to scientific discoveries about — for example — seagrass interaction with greenhouse gasses. Listening to the sonified data of those interactions on the track Dreams of Seagrasses opens cognitive and cultural possibilities of composing responses. And in listening well we prepare to respond to some other, quieting ourselves to attend to them, anticipating a future that might be made with them. “Listening is the invisible and inaudible enactment of the ethical relation itself,” writes the philosopher Lisbeth Lipari; “Upon it, everything depends.”5

This album emerges from research exchanges that have produced scientific papers, museum installations and art exhibitions, literary and philosophical studies, and community-led research. For each piece you will find a “composition note” written with the artist explaining how the track was made, followed by a “listening note” connecting ideas across tracks and inviting reflection.

– Willis Jenkins

2Dunn, David. “Nature, sound art, and the sacred.” The Book of Music and Nature (1997): 97.

3Van Dooren, Thom, Eben Kirksey, and Ursula Münster. “Multispecies Studies Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness.” Environmental Humanities 8.1 (2016): 1-23.

4Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016: 8. 5Lipari, Lisbeth. Listening, thinking, being: Toward an ethics of attunement. Penn State Press, 2015: 204.